Continuing on from the last blog here are the final four descriptions of the artworks in my new Ancient Ireland Land of Legend Portfolio One.

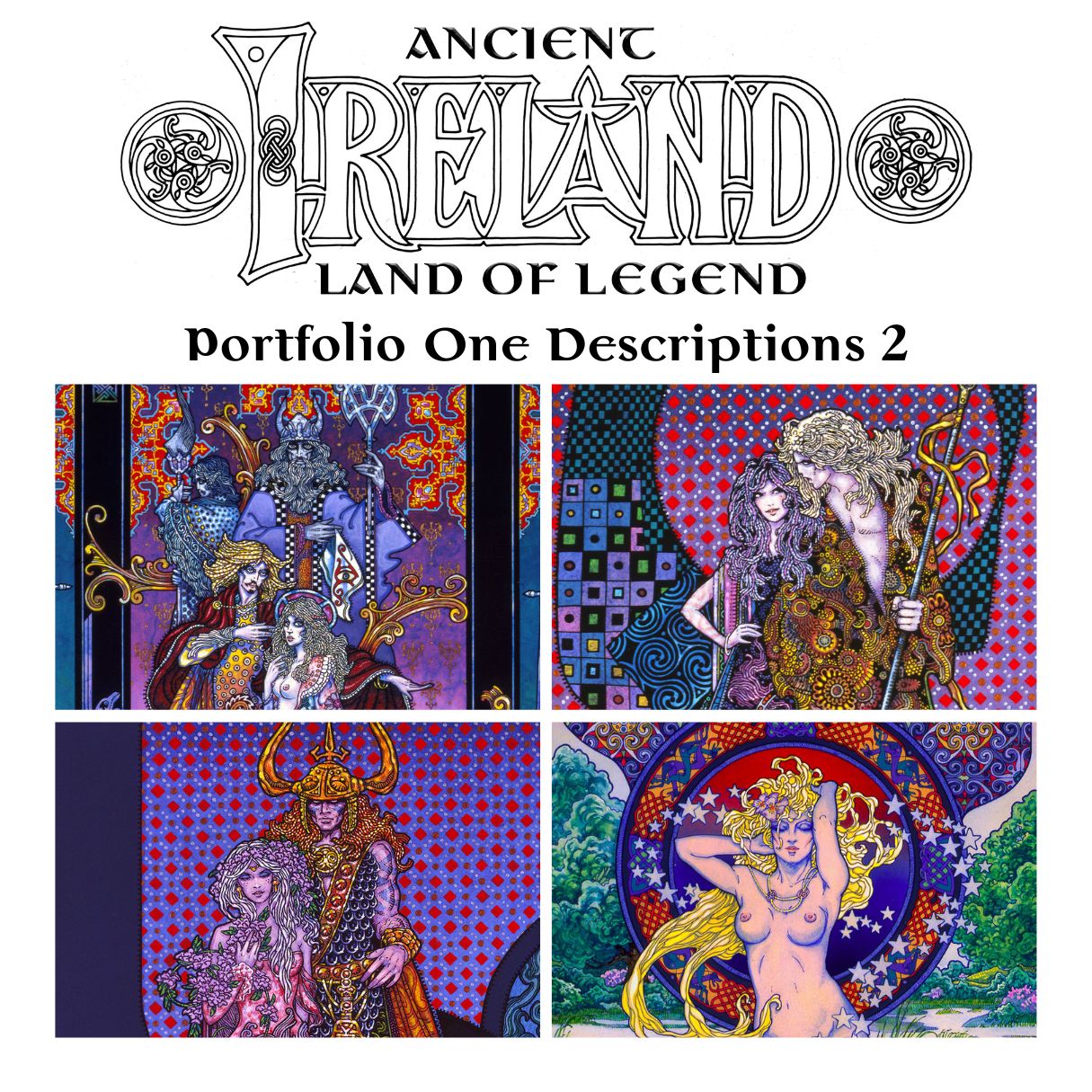

MORFÍS THE DRUID.

THE BACKGROUND.

I only ever published this seminal painting, which I personally believe to be my best work, once before, and that was in my book ‘ÉRINSAGA’, published in 1984.

Now it is time to do it justice with this stunning metallic print.

This work is heavily influenced by the master, Irish stained glass artist Harry Clarke, one of only two or three Irish artists recognised internationally but up until recently well ignored by our elitist, extraordinarily snobbish, self-replicating, Irish art establishment.

Now, thanks to the sterling work of writer and researcher Nicola Gordon Bowe this is no longer the case.

When businessman Lochlann Quinn donated a good number of original Harry Clarke book illustration masterpieces to the National Gallery things also began to change with new National Gallery publications of Clarke’s beautiful work lining their bookshelves for the very first time.

I was familiar with Clarkes ‘Geneva Window’ and lived near the then Municipal Gallery, now the Hugh Lane Gallery, where it was on display before being sold off and the money saved (£100,000) spent on a cheap blackboard by chancer Joe Bueys, who I knew from The Bailey pub, who laughed all the way to the bank. Quite rightly too.

Everyone involved in this charade should be deeply ashamed of themselves but you can bet they are not. I know that for a fact.

Our magnificent Geneva Window was exported to the Wolfson in Florida where I went to pay homage to it for the last time in 2007.

Luckily as a kid I had this on my way into town to admire and examine.

I do believe my art has been hugely influenced by the stained glass leading and line techniques. This is obvious in my work with often heavy dark outlines and finer detail inside those lines. Add the influence of American comic art and later the Japanese prints of the Ukiyo-E floating world.

THE PAINTING.

The painting depicts the mythical druid, seer and soothsayer, Mórfís, who came to Ireland with the fifth wave of invasion by the quasi-mystical race known as the Tuatha DéDanann, led by their chieftain Nuada, later known as Nuada of the Silver Arm.

The subject, Morfís the reknowned druid, looms large in the background while the foreground portrays a fanciful take on the shapeshifting seducer, the Morrigan, and her consort.

All purely imaginative and we know what happens when things are left to my imagination. There are too many cross-references to go into in detail here, but the two plumed warriors are holding a solar flag symbolising the one true creator god, the Aten, a nod to Scota/Meritaten, reputed daughter of ‘heretic’ Pharoah Akhenaken, who is buried in Ireland and this important north African influence is mentioned in our most ancient annals.

The plumed helmets and the twin horse decoration running across is intended to remind us of the influence of Thracian and Scythian culture on our various invading races who all seem inter-related and spring form the same source in Europe.

There are, if you look closely a few hidden codes and runes there too but have fun working them out.

None of this is meant to be historically accurate and artistic licence is my excuse.

For further research I suggest reading ‘The Origin of the Irish’, by J.P.Mallory ro reading the research of geneticist Dr, Lara Cassidy.

Looks like my lot, tall, rangy, freckly redheads came from the Poniac Steppes, or old Scythia as it was back then, in prehistory.

CONÁN OF THE FIANNA.

I was on a roll when I produced this work back in 1984. I was earning good money from my posters and books back then and that allowed me to really spend a bit of time on work I enjoyed and wanted to develop more.

This painting of the hero and warrior, Conann Maol of the Fianna Eireann, of the legendary Clann Baiscne, is one that worked well for me in terms of execution and was inspired by an earlier drawing of mine for a beautiful three colour silkscreen poster back in 1973.

The Fianna were bands of young warriors, who, for various reasons were unable to fit comfortably into the patterns of tribal society. As members of the Fianna they were free of their normal tribal obligations and so devoted themselves to hunting and mercenary warfare.

Their leader Fionn Mac Cumhaill (Finn McCool), was one of Ireland’s greatest warriors and a descendent of both the Tuatha De Danann and the Fir Bolg, two of the five tribes who came to Ireland in ancient times, conquered and were conquered in turn.

His son Oisin, after whom the Ossianic Cycle is named, was perhaps the greatest poet of the Fianna, is one of the very greatest of all the poets of Ireland and his work is still taught and read to this day.

Conán was the son of Morna, the slayer of Cumhaill, the father of Fionn.

On Fionn’s assumption of the leadership of the Fianna, Conán became one of his closest advisors and allies –while also becoming notorious as a great boaster and charmer. His warrior exploits became the stuff of huge admiration and sometimes gross hilarity.

His name was also Conan Maol, which is often mistranslated as ‘Conan the Bald’ when it is more subtle than that meaning ‘Conan the Blunt’.

He was also known as Mallachtán, which means insulter, as he often voiced how great he was, how deserving of respect and adulation, and how nobody else fared well by comparison, but there is little doubt he was a highly regarded and powerful warrior to have at your side in a battle or in an argument.

This very wild warrior did not take fools gladly and his sharp tongue is well recorded in the Fenian tales.

While he is renowned as a fierce fighter, his words lacked tact and delicacy but like his sword, came straight to the point.

In one wild encounter his skin is stripped from off his back and restored by the Shí who seal the scars by placing a sheep’s skin on his back which grows into his flesh becoming part of him, which probably did not help his quarrelsome humour.

It was never advised or wise to cross or jeer such a warrior. His enemies learned this lesson the hard way.

Certainly one interesting character, quite different and full of cynical humour, even his standard had a sharp briar on it to reflect his thorny nature.

How he died is not known but his grave lies in the Burren of Co. Clare.

DIARMUID AND GRAINNE.

The tale of the pursuit of Diarmuid and Gráinne is one of a number of epic but sad tales known as the ‘Great Sorrows of Storytelling’.

Diarmuid Donn Mac Duibne, ‘the master and charmer of all women’ was, by all accounts a very beautiful young man who took the heart of a certain Gráinne, a girl of great beauty herself -but already betrothed to his close friend and warrior comrade, Fionn Mac Cumhaill, the legendary leader of the greatest band of warriors ever to roam Ireland, known as the Fianna Éireann.

Fionn had no intention of letting go of such a beautiful bride-to-be s and relentlessly pursued the pair all over the countryside until finally Fionn and his army caught up with them and their escort but peace was agreed between the warring factions. But in his heart Fionn was still angry and unforgiving and when

Diarmuid was grievously wounded during a wild boar hunt Fionn allowed him to die. He went to draw water for him -for Fionn had the gift of healing -but each time Fionn let the water slip from his fingers rather than heal the gaping wound.

So it was that the beautiful and brave Diarmuid was finally parted from his beloved Gráinne.

This tale, the story of the doomed lovers Diarmuid Donn and the beautiful Gráinne, is one of the greatest of all the epic love stories in Celtic myth and legend and belongs to the Fenian Cycle of Early Irish Literature.

I have always been drawn to it and this final painting is my tribute to the great storytellers of antiquity.

I first drew this as a pen and ink work back in 1973 and reworked it, together with the sister work from that earlier period, Conánn of the Fianna, for my book ‘Érinsaga’ published in 1984.

The first versions of each artwork were black and white images and were much more simplified versions that were used as templates for a series of four-colour line art posters.

DAGDA AND THE WOMAN OF UINNIUS.

The Dagda was one of the great omnipotent deities of the early Celts, a celestial father-figure like Odin in the Viking myths.

The Dagda was also one of the principal leaders of the Tuatha De Danann and was credited with much wisdom though many of the myths often treat him as an over-weight object of fun and ridicule, with a weakness for beautiful women.

In a reamhschéal, a preamble, to the epic tale of the Second Battle of MoyTura recorded in the ancient annals, Dagda sets out to spy on the enemy Fomor battle lines. On his way through the province of Connacht, in the west of Ireland, he paused to drink at the river Uinnius and is startled to see a beautiful, voluptuous woman bathing naked in the river.

Without hesitation Dagda, who is recorded as a very large stout man, wades into the river in expectation of a sexual encounter. The woman teases him and remarks on his large girth but slowly he comes closer and ‘caressed her as intimately as the water’.

‘You are a witch’, he said at last’.

And you are bewitched’ she smiled’.

From that encounter the Dagda learns from this sorcerous water goddess the secrets of the opposition Fomorian armies and their battle plans for the final conflict to determine who will control the destiny of both tribes and the island of Ireland.

These ancient and extraordinary have be described by experts as ‘the earliest voices of European civilisation’ but cannot be accurately dated as they are written versions by trained scribes from a much older oral tradition of recording history in a memorable manner so that future generations can carry the story onwards, as they have done right up to the present age.

This painting caused a bit of a commotion at the time.

The naked water-goddess drew many comments, mostly complimentary, but of course in the Ireland of the 1970s there was a bit of tut-tutting but one friend of mine was annoyed at the strategically stars.

That was my call, not the publishers who would have preferred if the star was not there. I thought it actually added to the work and was kinda fun too.

The model never objected.

I was also aware of the fact that at the time, back in the skinny 70s this was a very well-rounded young woman, but she was hardly obese, just voluptuous.

One of the very few of my works that I have sold and boy do I regret it.

If I had the money I would buy it back immediately but it’s long gone and has changed hands too.

I do believe the present owner will take good care of it. I do hope so.

I think it is now in good hands but I’m not sure.

PS. There’s a little bit of mischief going on throughout this painting so check out the base to the right and start there.