THE CHE GUEVARA POSTER STORY.

PART 3

A pilgrimage to Rome.

I suppose it’s a natural reaction for most people who know my work and the iconic red and black 1968 ‘Viva Che!’ poster to think this encounter with Ernesto ‘Che’ Guevara, the most famous revolutionary in the world at that time, was life changing.

But that was not really the case until many years later.

Let’s start at the beginning:

What was I doing in Kilkee in the first place?

That part of the story comes from the summer of 1961 and touches on my last year in college in 1962.

Back then I was a boarding student in the beautiful and newly founded, Franciscan College, in Gormanston, County Meath, the Royal County.

For our final class year it was decided by the good Franciscan friars that there would be a pilgrimage to Rome but as the friars had a vow of poverty it was only just that the playing field must be level for all.

Each of us had to work to finance the trip, not the parents, as some were very rich old money, others were well off while my mom was a single working mother -and penniless.

Every spare cent she earned went on my education.

One of the friars, Father Godfrey, had connections in Kilkee, so me and another classmate, Gilbert Brosnan, were elected to go and get work and lodgings in the Royal Marine Hotel in Kilkee.

Now back then, as far as any Dubliner like myself was concerned, Kilkee was out there way west in the arsehole of nowhere on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean.

My mom absolutely loved the place so her enthusiasm was infectious and she had loads of friends there -and a relative, Mary Marrinan, a beautiful redhead my own age, was working in the Hydro Hotel near to the Marine so it looked like an exciting three month summer working holiday.

I had always worked during the summer hols since I was 9 when I picked fruit on Fruitfield farms in Donabate so this was normal for me. No one forced me I just wanted a few pence in my back pocket.

Even though I had never been there I felt I knew the place well and my mom and her lovely partner, Jack, often stayed in Johnny Redmond’s Strand Hotel just opposite the cliffs of Georges Point.

Besides, I was a Clareman myself, as was my mom, we were both born in Dublin but the Clare blood ran strong.

After a long train ride to Limerick myself and Gilbert got the green single-decker CIE bus which ran twice a week back then.

We arrived in Kilkee quite late and right opposite the bus stop was The Royal Marine Hotel.

We presented ourselves to a rather taken aback hotel manager, Mr. Haugh, who, it seems, knew nothing about hiring the two of us, but luckily it was peak season and the hotel was full so help was useful

Problem was Gilbert had zero experience while mine was limited to flipping burgers in Wimpy’s on the quays and the Rainbow Café in Dublin’s O’Connell street.

Not that it mattered as it turned out.

Within record time I was a barman and Gilbert was a waiter

so we were in business and earning nice money from tips in no time at all.

By some strange odd, coincidence I googled Wimpy Bar for this piece and found a very early photo of my lovely friend and collaborator, Philip Lynott, later of Thin Lizzy, with another old friend of mine, record store owner and now ti op promoter, Pat Egan, with John Farrell, the lead singer from The Movement, one of the very first bands I worked for way back.

Yep, three degrees of separation in Ireland works for me in this photo clipping.

Meanwhile back to Kilkee 1961 and the story.

Mr.Haugh, the manager, told us to start in the morning and led us to the kitchen for some food. We were starving and had only had a few home-made sandwiches left so we tucked in and cleared our plates at lightning speed. It all tasted delicious we were so hungry, and we felt a lot better too after such a long journey on the back roads, but it was all downhill from there.

Kilkee and Farting Cows

Our first five days were spent sleeping in a cowshed loft in the laneway at the back of the hotel.

The boss kindly gave us a double mattress to lay on top of the hay and a few blankets, but it was far from acceptable, even in Clare in 1961. It wasn’t the effin Famine and besides there were ticks everywhere and I knew they were dangerous if left unattended.

If you left them there you could get serious blood infections or Lyme disease so it was so important to leave them there until you had a match or a lit ciggie to smoke the little f**kers out of your skin slowly so their pincers came out too.

I knew this from my aunt in Kilcurrish, Ennis, where I stayed for about five months a few years earlier, sent there to escape a massive polio epidemic in Dublin.

I used to sleep in the fields on a warm night – I loved the sheer freedom and extreme latitude allowed me by my aunt and I slept always beside the calfs for warmth (they knew me well too) so blood-sucking ticks were a predictable outcome.

I never removed them until my aunt, Mary Darcy Lyons, was there to help with a lighted cigarette or even a match. We roasted the crap out of the blood-filled ticks until they withdrew their damn sharp fangs and squish they went once removed.

Yep, they left a mess of blood behind, my blood.

Now years later here I was in Kilkee and I was sleeping in hay again with flatulent cows going nonstop and their gigantic chainsaw farts had only one way to go, unlike in an open field, and that was upwards to the loft where we were trying to get some sleep.

This was not exactly what we had signed up for.

To be very honest we were unfazed and slept like bricks, dead to the world after long hours working in the dining rooms and serving in the bars of the hotel.

Talking to Gilbert, now a long-time neighbour in Howth near my own studio, only last week, he reminded me there were partitions in the barn and right next to us was a very pretty girl and her mattress on the straw floor. I think Gilbert tried his luck but she was already spoken for.

I only had kissed a few girls at the point so I left him to it -but I was determined that we could do better than a barn, a cute girl and farting cows for our sleeping quarters.

That’s when I decided to bluff Haugh, the boss, and get a bloody room for the two of us.

One morning as I started work, cleaning out the jacks ffs, I approached Haugh and explained to him that my dad was a big man in the trade unions and he, my fictional dad, told me that we were entitled to proper bed and board and proper pay rates.

All errant nonsense, I didn’t have a dad, he had legged it when I was five but hey I was tired of sleeping in a hayloft.

I don’t think he was too impressed and told me to get on with the work but I could see he was a bit worried and sure enough myself and Gilbert were given the smallest room at the back of the hotel that same day.

There was one bed for the two of us, which we rotated as his hours were different to mine, not that it mattered we were so exhausted by the time we hit the sack that we went out cold.

I will check with Gilbert but I think we slept head to toe, not side by side, which gave us more room. If I remember correctly it was a single bed too.

We also had some really lovely young girls in the rooms opposite and we would sneak them in. Nothing sexual back then, I wouldn’t have had too much of a clue what to do anyway, just fun and good company was enough.

That next morning after a decent night sleep I was dressed in my suit and a white shirt as instructed and doing my job on a Sunday morning of welcoming guests to the hotel standing outside on the Victorian verandas.

I was escorting some new arrivals to their rooms when this rather posh RAF type approached me and introduced himself.

It was Mr. Williams, who owned the hardware store next door and who seemed to be the real owner, very dapper and tweedy, rather British in accent, not looking unlike actor Terry Thomas from the British ‘Carry On’ movies, complete with a handlebar moustache.

He smiled and asked me an odd question:

‘Mr. Fitzpatrick, do you have an aversion to drink?’

Now what prompted his concern was my Pioneer pin stuck on my lapel along with my Fainne.

(The Pioneer pin signified I was sworn not to drink and the Fáinne denoted my ability to speak in Gaelic, our native tongue)

‘Not at all, I have no problems in that area, just don’t drink myself’.

And that is how I ended up as a barman in The Marine Hotel.

After a mornings training and a few learning errors I was ready and by lunch hour I was serving drinks.

Never even spilt or spoiled a pint either.

Kilkee in the Summertime

Now Kilkee was one vibrant little town in the summertime. There were reputably nearly 50 licensed drink premises back then, down to about 25 today. All of Clare and Limerick partied there with its all-nighter pub lock-ins to avoid the law and endless musical and dance nights.

There was one singer I liked enormously who had that ‘Peaky Blinders’ Brillianteened mop of hair and he sang his own version of Percy French’s famous ditty’ The West Clare Railway’

‘Are you right there Michael, are you right, do you think we’ll get there before the night?

but he often rendered a hilarious, salacious parody of a song which was a parody already. I’m printing the words out since it was my own mom’s favourite song and my own too back then. Here ya go:

‘Are ye right there, Michael, are ye right?

Do you think that we’ll be there before the night?

Ye’ve been so long in startin’

That ye couldn’t say for certain

Still ye might now, Michael

So ye might!

They find out where the engine’s been hiding

And it drags you to sweet Corofin

Says the guard: “Back her down on the siding

There’s a goods from Kilrush coming in.”

Perhaps it comes in two hours

Perhaps it breaks down on the way

“If it does,” says the guard, “by the powers

We’re here for the rest of the day!”

And while you sit and curse your luck

The train backs down into a truck’.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Are_Ye_Right_There_Michael.

The pub singers altered version I cannot remember exactly but I do remember these last lines:

’At Kilkee the sun shines like a jewel,

the scene is sublime, I’ll admit

But will sentiment pay for the fuel ?

And keep the line open?

Like shit!’

I always remember those lines and the locals loved the angry additions and cheered wildly, showing their anger at the loss of a lifeline as the railway was a local necessity long gone, further isolating all of West Clare for over a century.

Luckily some enthusiast recovered and restored the West Clare railway engine and we can see it in all its glory today.

For about a month myself and Gilbert worked like loonies, non-stop day and night, earning damn good money on top of our measly salary of a fiver a week.

Gilbert worked as the waiter and I was the barman so we didn’t spend that much time together as we slept completely different hours, he was on all day until about 10 at night when I mostly started.

Around that time as I was promoted to work during weekend lock-ins when the tips were deadly so things were looking up.

We met many of the great and the good of Connacht and Munster society during those long lock-ins but my favourite were the local permanent bar customer, Sam, a lovely guy who would sit at the bar nearly all day and kept me company when things got a bit dull.

My other favourite customer was Dermot Harris, the younger brother and manager of the very famous actor Richard Harris.

I never got to know Richard much at the time as he was a handball fanatic and spent his time bettering a ball against the Kilkee sea wall when he wasn’t hellraising and shouting at his mates, causing a little trouble but much entertainment, while Dermot was quiet, polite and liked to hang out at the bar.

He was not a heavy drinker like Richard and I remember him well, plus he was a great tipper.

Back then I had a habit of calling all the male customers ‘Sir’ -as in ‘What can I get you, Sir?.

‘Never call any one these people ‘Sir’, Jimmie, they will get ideas beyond their station, get their names right and you get a better tip’ he advised with a laugh.

Best advice ever, worked nearly every time and of course in a mad-busy Irish bar with layers of people clamouring for drinks and only two staff I made sure MY customers were never kept waiting.

During the days, which seemed endlessly long and sunny, as I didn’t start work until 12 noon or 10 at night, I hung out with Mike Williams, a really nice guy around my own age and a few local friends including a beautiful girl called Olive.

I had my first ever real crush on her.

She was gorgeous and had style but was way out of my league, I was a geeky, six-foot redhead with questionable style (I cringe when I look back) with a ducks-ass haircut and always with a cigarette staining my fingers but she took to me so we used to walk and talk a lot but I never got to even snog her.

It was all good clean puppy love, unrequited but powerful.

The local lifeguard was a Clareman with Italian lineage called Manuel De Lucia and I was lucky enough to date his stunningly beautiful younger sister later when I was back home in Dublin.

Unfortunately I took her to the Corinthian Cinema on the quays and sat her through two hours of a very earnest and worthy communist movie on the reconstruction of Warsaw after WW2.

She wisely legged it after that but I was beginning to find my feet and learning fast exactly what women did NOT want.

Commie movies were not high on their list of things to do on a date.

The year before I had a job as a hamburger chef which I hated. I worked in the Wimpy Bar on Eden Quay and was in the front window dressed in full chef regalia and that ridiculous chefs hat too.

All my youth I worked summer jobs as did all my friends and schoolmates and back then there was no free money, no ‘benefits’, nothing’ so if you wanted to eat, you worked or leeched of your Besides, it was a step up from fruit picking in Donabate, north Dublin, which I did every year on holidays in nearby Portrane.

Yep I was a worker bee from an early age.

Still am at the age of 79 and counting today.

By the end of that long, endless summer my college mate Gilbert had left and gone home back to Dublin and I was tired, bored and restless so one day I just packed my suitcase, said goodbye to everyone and started hitchhiking home.

The freedom I felt was only short of estatic. I was back on the road.

I loved walking and hitchhiking. I often asked a driver to drop me off early when I found them boring so each time was a cool new experience. I musty add that hitching in Ireland back then was safe as houses. There was no crime to worry about but we always were aware when hitching to look out for what we called ‘shirt-lifters’.

No need to explain that one I hope.

After about an hours walk in the sunshine and two short lifts I got a ride to Ennis and hitched back to my Auntie Mary’s thatched cottage at Fountain Cross, Kilcurrish, just outside Ennis and source of so many happy memories from years earlier.

Mary was so amazed to see me and burst out crying, welcomed back to her home and put on the kettle.

I had a massive meal of bacon, cabbage and potatoes and was on my way to Limerick after a few hours back hitching to Limerick where I finally got a train to Dublin.

My mom, who I had phoned from Limerick station, was relieved when I finally arrived at Kingsbridge Station (now Heuston Station) and delighted to see me safe and well.

I even had a nice suntan from walking and hitching around County Clare so after a very long 48 hours I was home, regaling her with my tall tales and funny stories.

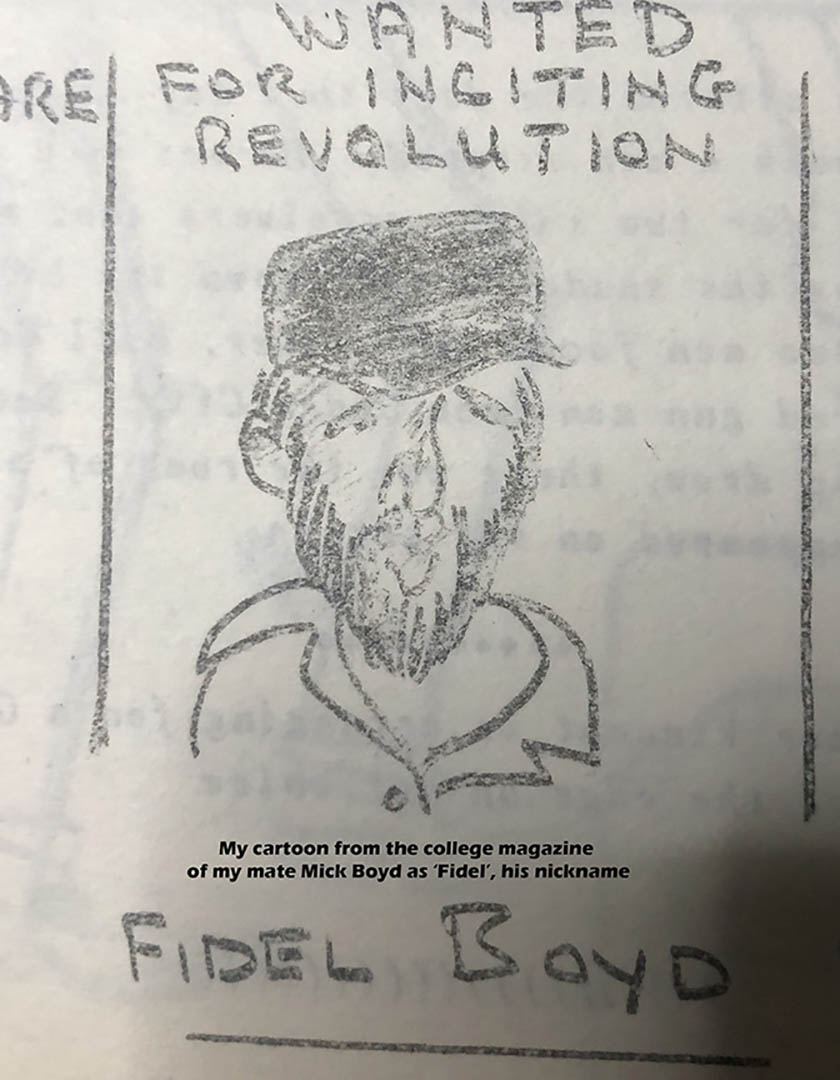

A few days later I was back in Gormanston College and while my best mate in the college, Mick ‘Fidel’ Boyd, knew well who Che was and was suitably impressed, hardly anyone else showed any interest in my Che story which was understandable.

It was a big deal for myself and Gilbert but that was it.

For a while I was nicknamed ‘Che Fitz’ by Mick ‘Fidel’ Boyd, but that died off in a short time thank heavens.

The other two photos are of the cover of Tally-Ho, the college magazine and the cover for1962 with a drawing of Saint Patrick by someone called ‘Fitz’ and a toon of my mate Mick Boyd by the same hand. All drawn on Gestetner waxed paper with a stylus so no wonder thye look damn crude but that was the tech we had in the college basement so we went with it.

Little did I realise this was just the beginning of a crazy story that led me to create the series of Che posters many years later and made my third image, the red and black ‘Viva Che’ 1968 poster such an icon.

NB: A little note on the very primitive Gestetner machine printing used for the college mag from ‘Australia Remember When’ Facebook pages:

Who remembers using the old Gestetner machines?

As I recall the Gestetner was long before photo copiers and was a stencil method duplicator that used a thin sheet of paper coated with wax which was written on with a special stylus that left a broken line through the stencil — breaking the paper and removing the wax covering. Ink was then forced through the stencil — originally by an ink roller — and it left its impression on a white sheet of paper below.

Some of the copying machines had a very strong ink/alchohol smell and I think we used to get a bit high on the fumes at times. All gone now of course, replaced by computers and photocopiers.

One last note.

After all the work and saving such good money I decided not to join the pilgrimage to Rome and bought a beautiful racing bike instead. Here I am with it, my pride and joy at the time.

Together with my mate and neighbour in Drumcondra, Mick ‘Fidel’ Boyd, I must have cycled every back road in North Dublin on that magnificent machine.

It was only a few short years later that Che Guevara came back on my radar when the western press announced his disappearance, his alleged execution by Fidel Castro and his reappearance in Bolivia.